The Virginia Calculator: Thomas Fuller, the Enslaved Mathematical Genius Who Defied Ignorance and History

He could calculate seconds in a year and a half in two minutes—in his head—while enslaved, illiterate, and never having seen a classroom.

His name was Thomas Fuller, though history also remembers him as “Negro Tom” and the “Virginia Calculator.”

Born in Africa around 1710—in what is now Benin—Thomas was kidnapped and shipped to America as a slave in 1724, when he was just fourteen years old. He would spend the next 66 years enslaved on a Virginia farm, working the fields from sunrise to sunset.

He never learned to read. He never learned to write. He never received a single day of formal education.

But Thomas Fuller possessed one of the most extraordinary mathematical minds ever documented.

Late in his life—when he was already in his 70s—two antislavery campaigners named William Hartshorne and Samuel Coates heard rumors about an enslaved man with impossible calculating abilities. Skeptical but curious, they traveled to meet him.

What happened next was documented by Dr. Benjamin Rush, a Founding Father and prominent abolitionist, who published their account in 1789.

The tests they gave Thomas Fuller would challenge anyone with paper, pen, and time. He did them in his head, in minutes, while elderly and exhausted from decades of labor.

First challenge: “How many seconds are there in a year and a half?”

Thomas closed his eyes. His lips moved slightly as he calculated. In approximately two minutes, he answered: “47,304,000.”

Correct.

Second challenge: “How many seconds has a man lived who is 70 years, 17 days, and 12 hours old?”

This calculation requires accounting for regular years, leap years, days, and hours—converting everything into seconds and adding it all together. A person with paper and pen might take fifteen minutes.

Thomas answered in 90 seconds: “2,210,500,800.”

One of the gentlemen, frantically calculating with paper and pen, told Thomas he was wrong—the number was too high.

Thomas replied immediately: “Stop, massa, you forget the leap year.”

When they added the seconds from leap years, their written calculation matched Thomas’s mental one exactly.

Third challenge: “Suppose a farmer has six sows, and each sow has six female pigs in the first year, and they all increase in the same proportion for eight years—how many sows will the farmer then have?”

This is exponential growth calculation—the kind of math that requires understanding geometric progression. In ten minutes, Thomas answered: “34,588,806.”

Again, perfect.

Dr. Rush noted that the longer time on this question was because Thomas initially misunderstood the wording, not because the calculation was harder for him.

Hartshorne and Coates were astounded. Here was a man who’d never been taught mathematics, who couldn’t read numbers on a page, who’d spent 66 years doing backbreaking farm labor—and he could outperform educated mathematicians using nothing but his mind.

But what struck them most was something else.

Despite being in his 70s, grey-haired and showing signs of age and exhaustion, Thomas was still sharp. They suspected his abilities must have been even more remarkable in his youth, when decades of hard labor hadn’t yet worn him down.

When Mr. Coates remarked that it was a tragedy Thomas had never received an education equal to his genius, Thomas replied with words that cut straight to the heart:

“No, massa, it is best I had no learning, for many learned men be great fools.”

Think about what those words reveal. Here was a man who understood his own brilliance, who recognized that formal education and actual intelligence are not the same thing, who’d maintained his dignity despite being enslaved and denied every opportunity.

Thomas Fuller died in 1790 at approximately 80 years old—still enslaved, still on that Virginia farm.

But before he died, his story served a crucial purpose.

Abolitionists like Dr. Benjamin Rush used Thomas Fuller as living proof against the racist pseudoscience of their era—the claims that African people were intellectually inferior, that slavery was justified because enslaved people couldn’t handle freedom or education.

Here was undeniable evidence: a man kidnapped from Africa, denied education, worked to exhaustion, and yet possessing mathematical abilities that rivaled or exceeded university-trained scholars.

No one could challenge his genius. No one could explain it away.

Thomas Fuller’s mind was a gift that slavery tried to bury—but couldn’t quite hide.

Today, we remember him not just for his calculations, but for what he represents: the countless brilliant minds stolen by slavery, the genius that persisted despite every attempt to crush it, the human potential that flourished even in chains.

How many other Thomas Fullers were there? How many remarkable minds were lost to slavery, never discovered, never documented, never given the chance to show the world what they could do?

We’ll never know. But we know there was at least one.

And his name was Thomas Fuller—the man who could calculate 47 million seconds in two minutes, who never forgot the leap years, who knew that wisdom and formal learning aren’t always the same thing.

The Virginia Calculator. Negro Tom.

But most importantly: Thomas Fuller, mathematical genius, who proved that brilliance cannot be enslaved—even when the body is.

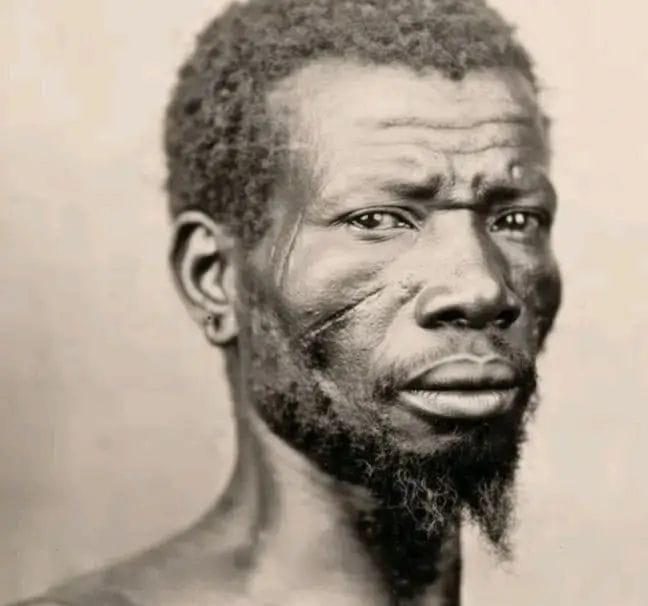

Thomas Fuller (c. 1710-1790)

Mental calculator. Mathematical prodigy. Living proof.