More than half a century after independence Africa still wrestles with the political ghosts of its past. The shape of its power the silence in its bureaucracy and the rhythm of its elections all carry echoes of an empire that never quite left. This piece traces how the colonial blueprint continues to cast long shadows on the continent’s leadership and how African societies are both victims and architects of that inheritance.

An Ancient Tree of Power

Power in Africa is not a new seed. It is an ancient tree whose roots run deep into the soil of conquest resistance and survival. Its trunk has been scarred by generations of rulers each carving their mark upon its bark. To understand the politics of Africa today one must dig beneath the slogans and elections down to the roots that were first planted by those who came to rule in the name of empire.

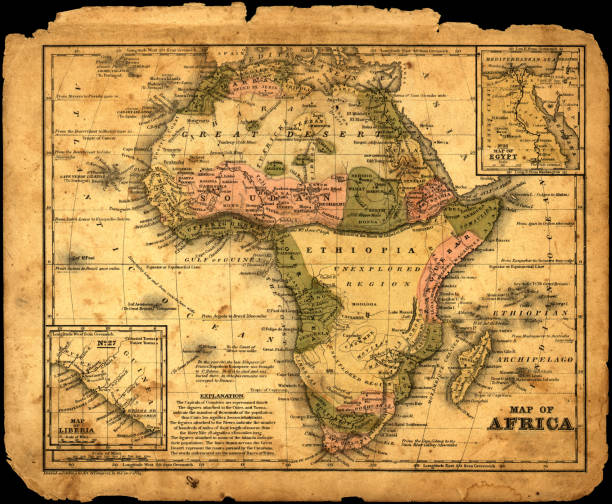

The Birth of Boundaries

When European powers gathered at the Berlin Conference in 1884 Africa became a map to be divided not a continent to be understood. Britain took the highlands France the deserts Belgium the heartland and Portugal the coasts. Borders were drawn across rivers and ridges without care for the people who lived there. Communities that had shared languages and markets for centuries woke up in different colonies. As historian Basil Davidson once wrote “The European powers did not create African nations they created African problems.”

The Machinery of Control

Under colonial rule governance became a machine of obedience. Chiefs were appointed or dismissed by governors. Taxes were enforced through punishment and laws were written in foreign tongues. Roads led from mines to ports not from villages to schools. The goal was not inclusion but control. The colonial state was designed to speak in one direction only downward.

Freedom with Chains Attached

To the colonizers this was administration. To the colonized it was humiliation. The institutions they left behind were rigid hierarchical and suspicious of dissent. When independence came it was both a victory and a burden. As Kwame Nkrumah declared on the eve of Ghana’s freedom in 1957 “We face neither East nor West we face forward.” Yet even as he spoke those words he was inheriting the same colonial framework of centralized power. The seat of the governor became the seat of the president. The old bureaucracy remained only its masters changed.

In Kenya Jomo Kenyatta preached unity after years of the Mau Mau rebellion but his government kept many of the same colonial laws that silenced opposition. In Congo the sudden exit of Belgium left chaos that swallowed Patrice Lumumba whose dream of independence lasted only months before his assassination. Across the continent the transition from colonial rule to self-rule was like replacing the driver without rebuilding the car. The engine of control kept running.

The Dreamers Who Tried to Rewrite the Story

Some leaders tried to rewrite the story. Julius Nyerere in Tanzania built Ujamaa a vision of African socialism rooted in communal values. He wanted to restore dignity to the village and break free from imported models of governance. Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso renamed his country “the land of upright people” and rejected the idea that Africa must follow Western blueprints. Yet both men faced internal and external resistance. Sankara’s revolution was cut short by bullets and Nyerere’s dreams strained under economic reality.

The Echoes of Division

Critics of modern African politics often trace today’s failures to those colonial roots. They argue that corruption ethnic rivalry and the obsession with power are fruits of that poisoned tree. The idea of “divide and rule” once used by Britain to control vast territories became a convenient tool for post-independence leaders to maintain loyalty through patronage. In Nigeria the tensions between north and south Christian and Muslim were shaped by colonial administration and still influence elections today.

The Argument for Responsibility

But there are others who argue that the past though powerful is not destiny. They remind us that six decades have passed since independence. They point to countries like Botswana and Ghana which have built stable democracies despite similar colonial histories. They argue that today’s failures are no longer imported but homegrown. “We cannot continue to blame colonialism for our mistakes” said former Tanzanian president Benjamin Mkapa. “We must take responsibility for the choices we make.”

Two Truths Entwined

Both views hold truth. History does not vanish it mutates. The colonial blueprint still influences how power is structured how wealth is distributed and how leadership is imagined. Yet African societies are not trapped in amber. Each generation has reshaped those structures in its own image sometimes reforming sometimes repeating. The past may have written the first draft but the present keeps editing.

The Baobab Metaphor

Perhaps the most powerful metaphor for Africa’s politics is the baobab tree. Its roots run deep its trunk is ancient yet its branches reach toward new light. Colonialism planted the soil with seeds of inequality and control but Africans have long tended their own gardens of resistance and reform. The question that remains is whether the tree of power will continue to grow in the shadow of empire or bend toward a more inclusive sun.

The Choice Ahead

The roots of power may indeed reach back to colonial times but they no longer decide the direction of growth. The continent stands at a moment of reflection. Its leaders and citizens alike must choose whether to prune the old branches or allow them to choke the new ones. Because history’s roots may hold the tree but it is the present that decides which way it leans.

Reflection

Writing about Africa’s history is never just an act of remembrance it is an act of reckoning. I write this as part of a generation that did not witness the colonial years yet still feels their echoes in policy in leadership and in the quiet frustrations of daily life. To understand power in Africa is to confront how easily it can be inherited without transformation. But it is also to believe that every generation holds the power to replant what was uprooted. The future will depend on whether we continue to water the roots of the past or dare to grow something entirely new.